It seems weird to introduce you to Freddy before officially introducing Edith but it also seemed a good time as it was his birthday the other day (when I started writing this post).

Frederick Edward Francis ‘Freddy’ Bywaters was born on June 27th 1902, the second child and eldest son of Frederick Sam Bywaters (1878 – 1919) and Lillian Bywaters (nee Simmons) (1874 – 1941). He had an older sister, Lillian and two younger siblings, Florence ‘Florrie’ and Frank ‘Frankie’. Freddy was the same age as Harold Graydon (Edith’s youngest brother) and friends with her other brother Bill. Another of Freddy’s friends, Bill West, remembers him fondly:

He was a hero to me. I asked him about my homework and he’d treat me with scorn: ‘You don’t know that!’ … I looked up to him, but he was so kind … what I thought of Freddy – it doesn’t mean that he thought anything of me. My appreciation is the greater because I didn’t have the qualities which he possessed … He was such a force to me which I would say exists to this day.

Aged 13, Freddy left school and worked as an ‘office boy’ for shipping companies. In February 1918, determined and ambitious, Freddy joined the merchant navy, sailing with P & O on the Nellore. He was not yet 16 but craving adventure he was now bound for India. Throughout the rest of his career with P & O Freddy would also sail to China, Australia, Japan and Port Said.

In 1920, Freddy first lodged with the Graydon’s for the duration of his shore leave. This is how he first encountered the adult, married Edith. Edith had known him throughout his childhood but, eight years his senior, she paid him little attention. That was all about to change.

The first known correspondence between Edith and Freddy dates to September 1920, which predates what is known to be the beginning of their affair (although at the trial they would both claim this was not the case) in June 1921.

On New Year’s Eve 1920, Freddy ‘jumped ship’ whilst docked at Tilbury, Rene Weis (Edith’s biographer and executor) believes this was a rash attempt to spend the night with Edith. Had it not been for Percy intervening on Freddy’s behalf, behaving so rashly would have cost him his job.

Whatever happened before June 1921, according to Edith in her letters, this was when the first “I love you” was uttered by Freddy to her. At the time, he was holidaying with her and Percy and her sister Avis in Shanklin on the Isle of Wight. On the return from the Island, it was agreed that Freddy would lodge in ‘the little room’ at the Thompson house. On Freddy’s nineteenth birthday, mere days later, he and Edith sparked their affair by becoming lovers.

For the majority of their affair Freddy was away at sea and they communicated by letter. Only three of Freddy’s letters survive. This one is from 1st October 1922, two days before the murder.

Peidi Darlint

Sunday evening, Everybody is out and now I can talk to you. I wonder what you are

doing now my own little girl. I hope that Bill [one of her younger brothers and

a sailor] has not been the cause of further unpleasantness darlint. Darlint

little girl do you remember saying ‘the hope for all.’ ‘Or the finish of all.’

Peidi the finish of all seems terrible even to contemplate. What darlint would

it be in practice? Peidi Mia I love you more and more every day – it grows

darlint and will keep on growing. Darlint in the park – our Park on Saturday,

you were my ‘little devil’ – I was happy then Peidi – were you? I wasn’t

thinking of other things – only you darlint – you was my entire world – I love

you so much my Peidi – I mustnt ever think of losing you, darlint if I was a

poet I could write volumes – but I [am] not – I suppose at the most Ive only

spoken about 2 dozen words today I don’t try not to speak – but I have no wish

to – Im not spoken to much so have no replies to make..

Darlint about the watch – I never really answered your question – I only said I wasnt cross.

I cant understand you thinking that the watch would draw me to you – where you

yourself wouldn’t – is that what you meant darlint or have I misunderstood you.

The way you have written looks to me as though you think that I think more of

the watch than I do of you – Tell me Peidi Mia that I misunderstood your

meaning.

Darlint Peidi Mia – I do remember you coming to me in the little room and I think I

understand what it cost you – a lot more than it could ever now. When I think

about that I think how nearly we came to be parted for ever – if you had not

forfeited your pride darlint I don’t think there would ever have been yesterday

or tomorrow.

My darlint darlint little girl I love you more than I will ever be able to show you. Darlint you are the centre – the world goes on round you, but you ever remain my world – the other part some things are essential – others are on the outskirts and sometimes so far removed from my mind that they seem non existent. Darling Pidi Mia – I answered the question about the world ‘Idle’ [idol] on Saturday – I never mentioned it.

(Sorry, that was long, but I think he’s a good writer).

Then came October 3rd, Freddy, having spent the evening with Edith’s family (the Graydons), made a ‘sudden’ decision.

I don’t want to go home; I feel too miserable. I want to see Mrs Thompson; I want to see if I can help her. […] I knew that Mr and Mrs Thompson would be together, and I thought perhaps if I were to see them it would make things a bit better. When I got into Belgrave Road I walked for some time, and some distance ahead I saw Mr and Mrs Thompson, their backs turned to me.’

Within a matter of minutes, the confrontation has taken place, Freddy has weilded his knife and Percy is dead. The following day, according to Freddy, he learnt from a copy of the Evening News that Percy was dead. He went to Edith’s family home where her father confirmed that Percy had been killed. Shortly after, two policemen arrived to take Freddy to the station ‘in connection with the Ilford murder’.

At the station, blood having been found on his coat, Freddy gave the follwing statement:

When I left the [Graydon] house I went through Browning Road, into Sibley Grove, to East Ham Railway station. I booked to Victoria which is my usual custom. I caught a train at 11.30 p.m. and I arrived at Victoria at 12.30 p.m. I then discovered that the last train to Gipsy Hill had gone; it leaves at 12.10 a.m. I had a few pounds in money with me but decided to walk. I went by way of Vauxhall Road, and Vauxhall Bridge, Kennington, Brixton, turning to the left, into Dulwich, and then on to Crystal Palace, and from there to my address at Upper Norwood, arriving there about 3 a.m. I never noticed either ‘bus or tram going in my direction. On arriving home, I let myself in with a latchkey and went straight to my bedroom. My mother called out to me. She said ‘Is that you Mick?’ I replied ‘Yes’, and went to bed. I got up about 9 a.m. and about 12 I left home with my mother. I left my mother in Paternoster Row about half past two. I stayed in the City till about 5. I then went by train from Mark Lane to East Ham, and from there went on to Mrs Graydon’s, arriving there about 6. The first time that I learnt that Mr Thompson had been killed was when I bought a newspaper in Mark Lane before I got into the train to go to East Ham. I am never in the habit of carrying a knife. In fact I have never had one. I never met a single person that I knew from the time that I left Mrs Graydon’s house until I arrived home.

Once the police had searched Freddy’s home and found letters from Edith, they put two and two together. At the station, Edith was told by Inspector Hall that Freddy had admitted to the murder. Edith, who had not mentioned Freddy in an attempt to ‘shield’ him, came clean.

Hall then tells Freddy that both he and Edith are to be charged with ‘wilful murder’. On hearing this, Freddy tells Hall that Edith ‘was not aware’ of his ‘movements’ on the night of the murder and gave another staement:

I wish to make a voluntary statement. Mrs Edith Thompson was not aware of my movements on Tuesday night 3rd October. I left Manor Park at 11 p.m. and proceeded to Ilford. I waited for Mrs Thompson and her husband. When near Endsleigh Gardens I pushed her to one side, also pushing him, further up the street. I said to him ‘You have got to separate from your wife’. He said ‘No’. I said ‘You will have to’. We struggled, I took my knife from my pocket and we fought and he got the worst of it. Mrs Thompson must have been spellbound for I saw nothing of her during the fight. I ran away through Endsleigh Gardens, through Wanstead, Leytonstone, Stratford; got a taxi at Stratford to Aldgate, walked from there to Fenchurch Street, got another taxi to Thornton Heath. Then walked to Upper Norwood, arriving home about 3 a.m. The reason I fought with Thompson was because he never acted like a man to his wife. He always seemed several degrees lower than a snake. I loved her and I couldn’t go on seeing her leading that life. I did not intend to kill hm. I only meant to injure him. I gave him an opportunity of standing up to me as a man but he wouldn’t. I have had the knife some time; it was a sheath knife. I threw it down a drain when I was running through Endsleigh Gardens.

Despite Freddy’s attempts to rid her of blame, later, both he and Edith are charged with murder. The case is heard in Stratfords Magistrates Court, during which time Freddy is held at Brixton and Edith at Holloway. Once it is decided that the case will be heard at the Old Bailey, Freddy is taken to Pentonville.

The trial of ‘Thompson and Bywaters’ begins on 6th December 1922 and lasts until the 11th of December.

When put in the witness box, Freddy’s mother describes him as ‘One of the best sons a mother ever had.’ James Douglas writes of Freddy:

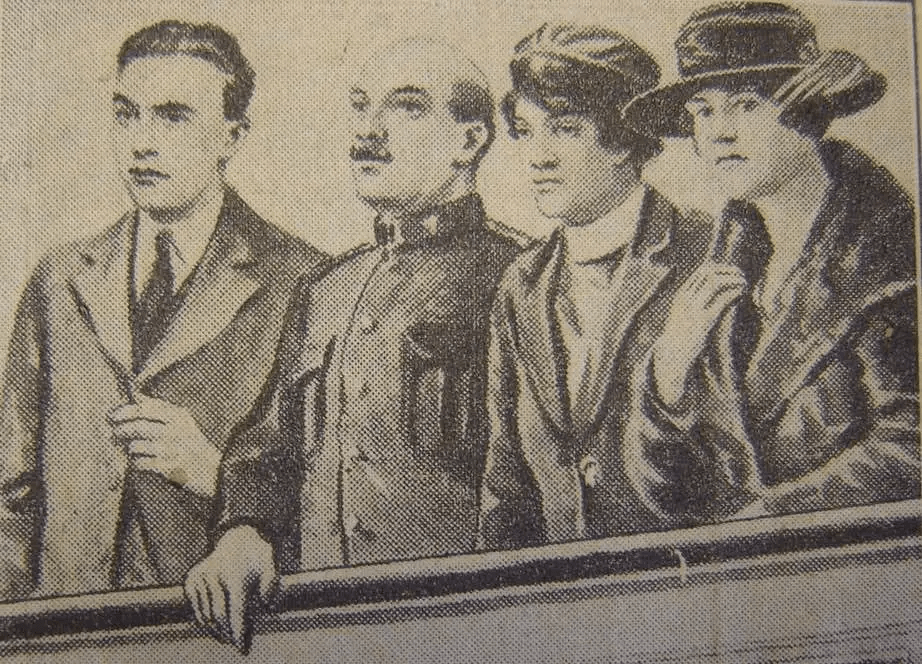

And what of the boy? Frederick Bywaters is a handsome youth, with a clear skin, finely carved profile, a trenchant, high forehead, brilliant eyes, and a great wave of thick brown hair brushed back high from his white brow. He is virile and vigorous in his gait, walking with a firm step and swinging arms.

This it is that throbs all day in court – youth in the toils of destiny, youth caught in the net of circumstance.

At the trial, Freddy could have defended himself by claiming that he had been led astray by Edith, a woman older than him, but he refused to take this stance.

When the guilty verdict is given and Freddy is given a chance to speak, he says: ‘I say the verdict of the jury is wrong. Edith Thompson is not guilty. I am no murderer. I am not an assassin.‘

The appeal process begins, a petition for reprieve is got up by the Daily Sketch. Freddy’s mother writes:

I am appealing to the hearts of all of the mothers of the nation to give me their help in getting a reprieve for my boy. You who have dear boys of your own will I am sure understand the terrible agony I am now suffering, and my great anxiety for his life to be spared. His father gave his life for you & yours, don’t let them take my boy from me. From a brokenhearted mother.

On 3rd January, Freddy makes a plea for his and Edith’s lives by writing to the Home Secretary, saying of Edith:

She is not only unjustly condemned but it is wicked & vile to suggest that she incited me to murder. God knows that I speak the truth when I say that there was no plan or agreement between Mrs Thompson & I to murder her husband. I can do no more, sir, than ask you to believe me – the truth – & then it is for you to proclaim to the whole world that Edith Thompson is ‘Not Guilty’ & so to remove the stain that is on her name.

The appeal having failed, Freddy’s mother writes to the King:

Your Majesty

I do humbly appeal to you to spare the life of my son Fredk. Bywaters,

now lying under sentence of death.

I am driven mad with anxiety, so I take this step as the last resource,

and implore your Majesty to grant me this request.

Had my poor boy a father to advise him this terrible thing would never

have happened, but my husband made the supreme sacrifice in the Great War,

leaving me with a family of four young children to support.

I have done my best for them and brought them up respectably.

Freddy, my eldest boy, went out into the world at the age of thirteen and

a half years. When only fifteen he joined the Merchant Service (he was not old

enough for the Army) and stayed with the P. and O. until Sept. 23 of this year,

his character all the time being excellent.

He has always been the best of sons to me, and I am proud of him, but

like many other boys of his age he fell under the spell of a woman many years

older than himself, who has brought all this terrible suffering on him.

Your Majesty, I implore you to spare his young life. I have given up my

husband. For God’s sake leave me my boy.

On 6th January, Freddy, visited by family, again insists upon Edith’s innocence:

I can’t believe that they will hang her as a criminal! … I swear she is completely innocent. She never knew that I was going to meet them that night. If only we could die together now it wouldn’t be so bad, but for her to be hanged as a criminal is too awful. She didn’t commit murder. I did. She never planned it. She never knew about it. She is innocent, innocent, absolutely innocent. I can’t believe that they will hang her.

Of himself he says: ‘I have not met with justice in this world, but I shall in the next. But I hope I shall die like a gentleman. I have nothing to fear.’

On the 8th of January, Freddy writes a letter asking the recipient to ‘love’ Edith and remmeber the two of them by going to their table at the Holborn restuarant (for a post that featured that letter see here.)

Freddy spends his last night talking with the governer of Pentonville, who remembers him:

‘Bywaters looked to me such a fine upstanding lad, with bright blue eyes and fair hair – a typical English boy. And his manner was exactly what you would expect, quiet, respectful, and thankful for any little kindness. His eyes showed that he had suffered much more than one usually does at that age. I thought, ‘What a strange thing: this boy, if he had not done that mad action for the sake of a woman, would, I feel certain, have turned out a good citizen.’ He was not a murderer at heart; it was due to the terrible emotion that possessed him at that time. I liked the boy. […]

When he came to my room, he thanked me in a shy way for being so kind to him. I saw he was relieved to have even a short time with me, away from his thoughts. He said, ‘I thank you, sir.’ He sat down, and I started speaking to him about his travels, and then he told me how beautiful were the colours of the Aurora Borealis, and the wonderful sunsets, and about the strange lands he had visited. He was visualising and telling me of some of these beautiful places, and the many journeys he had made to them’.

The following morning, with ‘great fortitude’ Freddy prepares himself. He dresses smartly and ‘recieves Holy Communion’. At 9am, after shaking hands with his executioner, Freddy is hanged. His fortitude and composure in the face of death has ‘become a legend’ at Pentonville. As well beleiving utterly in Edith’s innocence, Freddy did not see himself as a murderer. Today the murder might be considered a crime of passion.

‘I had no intention of killing him, and I don’t remember what happened. I just went blind and killed him. […] The judge’s summing up was just, if you like, but it was cruel. It never gave me a chance. I did it, though, and I can’t complain.’

He took someone’s life, which no one has any right to do, but it was not done with malicious intent and he paid the price. I can only hope to be as brave as he was when it came to it.

Leave a comment